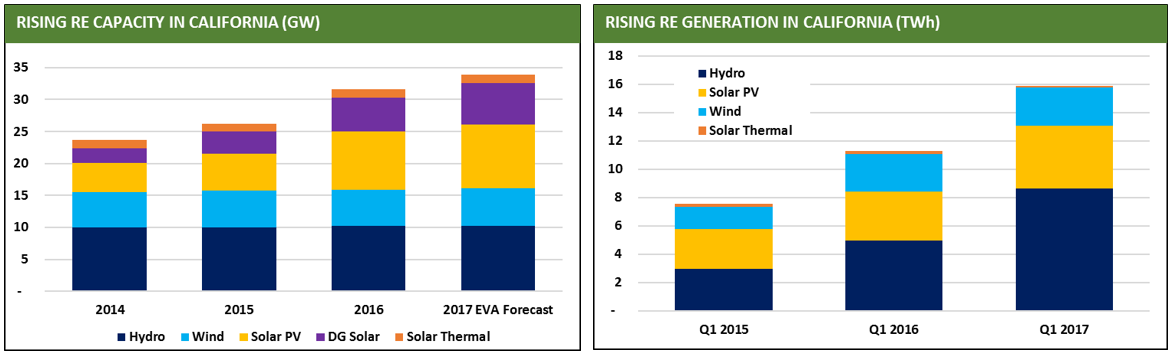

After suffering through several years of severe drought, California experienced record rainfall in late-2016 and early-2017, sufficient to fill previously depleted reservoirs. Simultaneously, the state brought on an additional 5.3 GW of solar capacity in 2016, bringing the total to 10.3 GW to go along with 5.7 GW of wind capacity.

As a result, renewable energy (RE) generation in California has surged through Q1 2017. The output has been so high that mid-day wholesale power prices have dipped into negative territory several times. Furthermore, CAISO reports record high levels of RE curtailment (i.e., forcing available generation offline). More than 60 GWh of available generation was curtailed in February and 80 GWh in March, more than double the curtailment last spring. Curtailments are likely to increase even further in April, though data is not yet available.

Curtailment of RE is not a wholly new phenomenon. In Texas, wind generation has been curtailed, to varying degrees, since the mid-2000’s, reaching a peak of 17% in 2009. More recently, rapidly rising wind generation in SPP and MISO has caused modest curtailment in those regions, as well.

However, the ongoing California experience is of a different sort, as it has been utility scale solar that is most commonly curtailed. Furthermore, while wind curtailments are most common during periods of high wind and very low demand (i.e., 2-4AM), solar curtailment in California is occurring in mid-day, when total demand is quite robust.

On an absolute level, only a small fraction of total solar generation is being curtailed—in March, curtailments represented less than 3% of total solar generation. In addition, the issue is largely restricted to the shoulder seasons and will be less pronounced moving into summer, as high AC demand, falling hydro levels and reduced wind output will render negative mid-day power prices extremely unlikely.

Yet the outcome demonstrates the rapidity with which high RE states are encountering integration issues that until recently, appeared many years away. For a state like California, which has a 50% RE target set for 2030, the experience of early-2017 is but a glimpse of things to come, as the integration challenges, while solvable, will continue to mount.

Curtailment would appear to be an unfortunate outcome for any generator, but CAISO’s process ensures generators are compensated. As signs of oversupply appear, CAISO allows generators to make “decremental bids” in which they name the price it would take for them to reduce output (i.e., accept being curtailed). According to CAISO, this method is typically sufficient to rid the market of oversupply.

If oversupply remains an issue, CAISO will pursue “self-scheduled cuts” that specifically target areas of high congestion for curtailment. CAISO then has a final option of “exceptional dispatch” in which it orders a specific generator or group of generators to cut output. Curtailment of this sort is exceedingly rare, occurring only a few times per year.

Given the general effectiveness of the initial decremental bid process, it is clear why utility scale solar is the most common generation source that is curtailed. Nuclear is incapable of ramping on and off on short notice, and hydro is often running in spill mode in spring, meaning generation cannot be turned off.

Gas is more flexible, but costs are still relatively high and they often must run at minimum levels, especially if they are to meet the considerable and rapid ramp-up of demand in the evening, when solar generation stops. Even if possible from a technical standpoint, many of the large generators also have contractual obligations that reduce their flexibility in choosing whether to participate in the decremental bidding process that precedes curtailment.

Finally, wind is more likely than solar to keep operating in order to take advantage of the Production Tax Credit (PTC), which rewards actual output. Solar projects, in contrast, typically opt for the Investment Tax Credit (ITC), which is not dependent on generation.

The net outcome is that solar generators in California often offer the lowest decremental bids (typically less than $20/MWh) and are thus most often selected for curtailment.

As more solar comes online, curtailments are likely to increase. Solar capacity additions—driven by the state’s aggressive RPS objective—could even create a paradoxical spiral in which increased curtailment actually hinders compliance with the RPS.

Recognizing this, California is bolstering connections with the broader grid in the Western U.S., including a steady expansion of its Energy Imbalance Market. Already, many of the power exports to surrounding states occur during mid-day, when curtailment is most pronounced. California also has aggressive battery storage goals, which—in theory—will allow a portion of solar generation to be shifted beyond mid-day.

Yet challenges will persist. Solar costs continue to fall, meaning the high rate of solar installations is likely to continue. Distributed Generation (DG, or rooftop PV) is also growing rapidly in California and CAISO does not yet track generation from these sources, which adds a layer of unpredictability to its efforts. As a result, solar curtailment in CAISO through early 2017 is an early sign of things to come as California continues its aggressive decarbonization efforts.