Rooftop PV installations have soared in the U.S. over the past several years, but activity has been heavily concentrated in just a few states offering strong policy support. Retail net energy metering (NEM), which allows the homeowner to sell surplus solar power back to the grid at retail rates, has been a particularly critical driver of rooftop PV development. The policy has long been controversial, but recent activity in several key states suggests a middle ground consensus may finally be emerging.

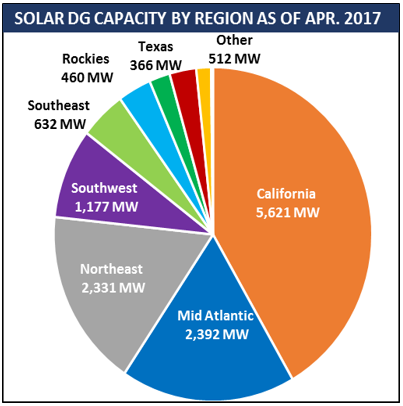

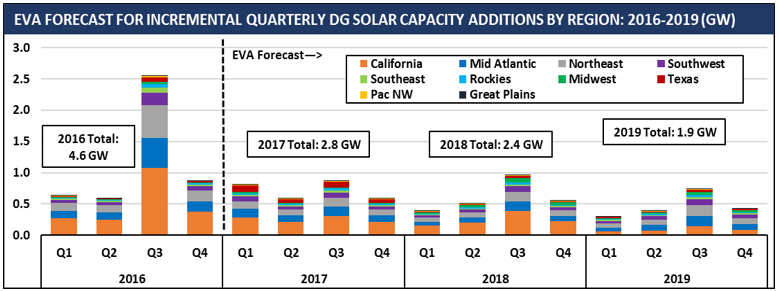

Rooftop PV capacity, also known as distributed PV generation (or DG), has risen from 2.9 GW in 2013 to 14.2 GW as of May 2017. The pace of development has fallen behind utility scale solar, which now totals 23.1 GW, but has still been remarkably rapid. Well over a million U.S. homes and commercial businesses now have rooftop PV installations.

There have been many drivers of DG capacity growth, including sharply falling installation costs, the widespread availability of third-party leasing options, state-level Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS), high solar renewable energy credit (SREC) prices and the continued extension of the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC).

Yet few drivers have proven more critical to rooftop PV development than the availability of retail net energy metering (NEM). Nearly every state allows surplus solar generation to be sold back to the grid; the key differentiator is whether it’s sold back at the retail rate, or a rate closer to the wholesale rate. If retail NEM is allowed, the economics for rooftop PV installations can be quite positive, especially in states with higher than average retail power prices.

It’s not surprising that California, which combines a strong solar resource with retail NEM (not to mention an aggressive RPS), is the clear leader in rooftop PV capacity—with 5.6 GW, it comprises nearly 40% of total U.S. capacity. Yet other leading states show how critical retail NEM is to rooftop PV development. New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Maryland all possess poor solar resources, but with high retail power prices and retail NEM, each has experienced considerable expansion of rooftop PV (though as in California, aggressive RPS targets and high SREC prices have helped, as well).

While certainly a strong driver of rooftop PV growth, retail NEM has always been surrounded by controversy. Beyond the technical considerations of adding a large amount of behind-the-meter generation, retail NEM is at the heart of political questions about how costs for grid maintenance should be distributed.

More specifically, opponents of retail NEM have long argued that the policy allows homeowners with rooftop PV to avoid paying their fair share of costs for maintaining the transmission and distribution grid. In most jurisdictions, such costs are rolled into the retail rate, thus the less net energy used, the less paid for the fixed grid infrastructure. Because rooftop PV owners remain entirely reliant on the grid (i.e., at night and on cloudy days), opponents argue they must still pay their fair share for its upkeep—failure to do so unfairly shifts costs to consumers without rooftop PV.

Further, the threat of cross-subsidization is particularly concerning to some policy makers due to the socio-economic dynamics at play. Because rooftop PV owners tend to skew toward higher income demographics, the cross-subsidization may be highly regressive in effectively shifting costs from the affluent to lower-income ratepayers.

Debates over retail NEM have popped up throughout the country, with more than 20 states reviewing their NEM policies, and a few have already taken action. In Nevada, the specter of regressive cross-subsidization was one of the key pillars of its decision, in late 2015, to eliminate retail NEM. It switched to lower compensation rates for rooftop PV owners (i.e., closer to the wholesale price or avoided cost) and didn’t grandfather-in existing rooftop PV owners.

The Nevada experience likely provides the most guidance for the future trajectory of state-level NEM policy. Eliminating retail NEM outright was highly controversial and quickly drew backlash. The impact on the state’s rooftop solar industry was immediate, with several major installers sharply reducing operations or leaving the state.

The controversy refused to fade and in June 2017, the state legislature (voting almost unanimously) changed course and re-established retail NEM for existing rooftop PV owners and agreed to allow new customers sell excess power back to the grid at 95% of the retail rate. This will gradually be stepped down to 75% of retail as new capacity is added.

Nevada is not alone in recognizing the perils of rapidly eliminating retail NEM. California, in 2015, agreed to keep its NEM structure largely in place through 2019. More recently, New Hampshire largely did the same, at least temporarily, as it continues to study the value of solar. Many states are likely to eventually stepdown compensation from full retail NEM, and/or add minor fixed costs for rooftop PV owners to ensure adequate payment for grid services. But as rooftop PV becomes more popular with a broader set of voters, few will be willing to replay the Nevada experience and set forth policies that would have an immediately negative effect on solar PV installations.