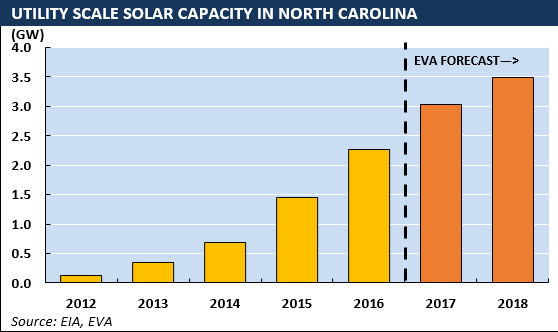

Renewable energy development in the Southeast U.S. has been largely non-existent, with the notable exception of North Carolina. Even there, wind development has been scarce, but the state has emerged as the nation’s second largest state for utility scale solar, behind only California. Having added 828 MW in 2015 and 758 MW in 2016, North Carolina has already added 493 MW in 2017, bringing total solar capacity to 2.8 GW (rooftop PV has been much slower to take off; the state has only 119 MW of DG capacity). While this still leaves the state far behind California (which has 10.2 GW of utility scale solar) it has a sizeable lead over Arizona (2.0 GW) and Nevada (1.7 GW), which round-out the top-4 solar states in the U.S.

North Carolina is even farther ahead of neighboring states in the Southeast. Total utility scale solar capacity in Georgia is only 981 MW (of which 741 GW was added in 2016), while development in Virginia (117 MW), Tennessee (70 MW) and South Carolina (42 MW) has been exceedingly limited.

Most states in the Southeast have similarly high solar resource qualities, but development in North Carolina has progressed due to several distinguishing policy dynamics not present in neighboring states. Most obviously, North Carolina is the only the state in the region with a Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), requiring 12.5% of retail sales to be sourced from qualifying renewable energy sources by 2021 (requirements for munis and co-ops are lower).

Until early-2016, the state also offered a generous 35% Investment Tax Credit (ITC) for in-state renewable energy projects, including solar PV. Notably, that tax credit could be used jointly with the 30% federal ITC, resulting in effective project costs coming in at a 65% discount. While the state ITC expired in 2016, the federal ITC persists.

Equally important however, if less commonly recognized, is the role North Carolina’s PURPA (Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act) design played in driving solar development. PURPA harkens back to 1978 and requires regulated utilities in any given area to buy power from small generating projects, also known as qualifying facilities (QFs), at the corresponding state’s designated avoided cost rate.

PURPA is a federal law, but states have discretion over some components, including setting the avoided cost rate and the duration of PPA contracts. In North Carolina, the avoided cost rate was set relatively high and was offered to independent generators for 15 years—longer than in many other states.

The net result was that a rush of solar developers, taking advantage of the federal and state tax credits, could profitably develop projects at the avoided cost rate locked in under long-term PPA. While PURPA has been a driver of solar growth in a few other states (including California) it has been particularly vital to solar projects in North Carolina, where approximately 80% of solar capacity has been developed via PURPA.

The dynamic has not been without controversy. Duke Energy, the primary utility in North Carolina, has long expressed frustration with the state’s PURPA structure, saying it is often required to sign high-cost PPAs for power it doesn’t need, or in locations far from demand centers.

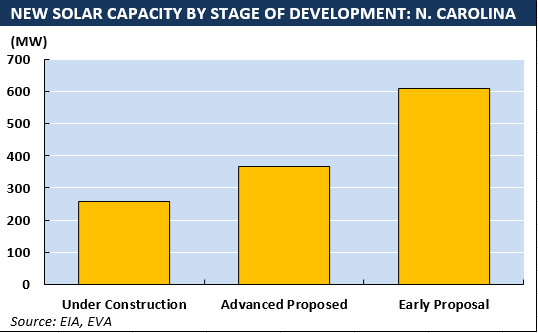

In July, after months of negotiations, the North Carolina legislature passed, and the Governor signed into law, a bill that significantly alters the role PURPA plays in driving solar development. Under the legislation, projects less than 1 MW will still be eligible for fixed-price PURPA contracts, but the duration was shortened from 15 years to 10 years. More importantly, the bill requires larger QFs to apply via a competitive bid process, which is designed to lower costs. Over the next few years, auctions will be held for 2.7 GW of new large-scale solar projects. This capacity will be in addition to the 259 MW of solar currently under construction and the 977 MW already in the proposal queue.

The outcome, negotiated in a purple state between a Republican legislature and a Democratic governor, required compromises from both sides, but was generally well received by the various stakeholders. As such, it represents the viability of informed renewable energy policymaking and stands in contrast to controversial outcomes in states (e.g., Nevada) where whipsaw decision-making served only to generate more uncertainty regarding renewable energy development. Perhaps more acutely, however, the outcome shows how dramatic cost declines have pushed the solar industry ever-closer to competing without pronounced policy support. Combined, the new legislation and falling costs seem set to ensure the continuation of strong solar development in North Carolina.

Want to read more? Visit our renewable energy page to see EVA’s full coverage of the U.S. renewable energy market and download a free copy of our Quarterly Renewable Energy Outlook!