Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) now exist in 29 states plus the District of Columbia. Thus far, all states have been able to meet their rising targets, albeit by very different compliance mechanisms. The seeming success of the programs has driven the more recent trend of states extending and expanding their RPS objectives, measures that have typically passed with relatively bi-partisan support. Yet, the cost and feasibility of increasingly aggressive targets remains an open question.

State-level RPS programs have been in existence since the early-1980s (starting with Iowa in 1983), but became increasingly common in the early- and mid-2000s as a means to reduce carbon emissions and spur in-state job growth. Program design differs widely between states, but the standards generally require a percentage of retail electricity sales to be sourced from qualifying renewable electricity (RE) generation sources.

Every state has so far successfully kept pace with its RPS targets, either through actual in-state generation or by sourcing RE, or renewable energy credits (RECs), from other states with more generation and/or higher quality resources.

The programs, along with the continued (if intermittent) availability of the federal investment tax credit and production tax credit, have been the cornerstone of RE development in the U.S. With the ITC and PTC set to phase-out over the next few years, and the Clean Power Plan soon to be abandoned under the Trump administration, state RPS targets will emerge as particularly vital drivers of RE development.

A few RPS programs have been challenged (notably in West Virginia, Kansas and Ohio, where programs were repealed, made voluntary or stalled, respectively), but most have emerged with relatively stable bi-partisan acceptance.

The more common trend has been for states to extend and expand their RPS objectives. In 2015, Hawaii, California and Vermont all enacted considerable RPS extensions. Hawaii extended its goal to 100% renewable energy by 2045, including 30% by 2020. California extended its target to 50% RE by 2030, a considerable increase over its previous 33% by 2020 goal. Not to be outdone, Vermont converted its non-binding RPS “goal” to a mandatory standard, requiring 75% RE by 2032.

The trend continued in 2016, with New York finalizing its 50% by 2030 Clean Energy Standard and Oregon upping its RPS target to 50% by 2040. Washington DC also extended its target to 50% by 2032 and Michigan raised its objective to 15% by 2021 (up from 10%). Illinois passed legislation to better encourage the use of in-state resources to meet its 25% by 2025 target, while in Ohio, Governor John Kasich vetoed a bill that would have stalled Ohio’s 12.5% by 2025 target (the Ohio program had already been stalled for the past two years).

It is notable that several of the states that have recently extended and expanded their RPS programs (VT, OH, IL and MI) have Republican governors—albeit typically with Democratic legislatures.

In these states, the Governors’ and much of the public support was driven not so much by the prospect of emission reductions but by the perceived economic and employment benefits associated with in-state RE development. Those arguments, of course, are not universally accepted, and a few state governors (namely Governor Hogan in Maryland) have opposed extensions. Yet, the trend is clear—RPS programs enjoy relatively bi-partisan support and states have thus far had little difficulty meeting their objectives.

It is important to note, however, that actual RE penetration in most states—even those with aggressive RPS targets—remains quite modest. California only recently exceeded 20% RE penetration (excluding rooftop PV), while New York renewable energy totals less than 10% (excluding hydro) of total retail electricity sales. Indeed, most states in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic have RE penetrations hovering near 5%, far below their long-term RPS targets of 30%, 40%, or even 50%.

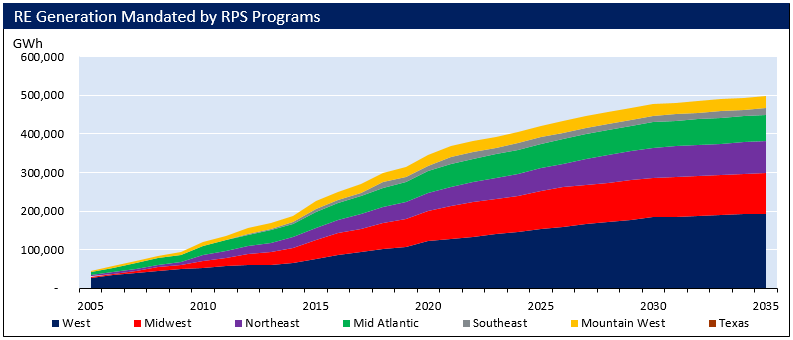

Thus, most RPS programs are still in the early stages and the feasibility of the long-term targets remains an open question. For many states, RPS requirements greatly outpace expected demand growth, meaning some existing generation will need to be displaced.

RE costs (especially for wind and solar PV) have fallen dramatically over the past several years but in most places, costs are still higher than CCGT additions and are certainly more costly than incremental generation from existing sources. Consumers, ultimately, must bear these costs in some form and as the programs expand, so will costs (e.g., REC prices) and potentially, opposition.

For states with limited resources and/or land availability, meeting their targets using in-state resources may become particularly difficult and expensive. It is likely that some states will move to increase program flexibility, namely to allow compliance from more out-of-state sources. Variability and intermittency will inevitably emerge as challenges, as well—first in California then spreading to other states (these issues will be explored in detail in subsequent newsletters).

Given these impending challenges, we expect few states to issue RPS expansions in 2017. Activity will certainly be absent in states with Republican governors and legislatures. In several states, the RPS will likely be allowed to expire as scheduled, typically in the 2020 timeframe. Even states with Democratic leadership will likely adopt a “wait and see” approach, closely monitoring how states with aggressive targets handle any emerging difficulties before they approve any additional modifications to their existing programs.