After months of anticipation, EPA’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) – one of the most watched environmental regulations coming out of Washington, DC – finally had its first day in court on September 27. This newsletter summarizes the Clean Power Plan and the legal issues at stake, previews the remaining schedule for the litigation, and highlights results from EVA’s State CPP SIP Survey.

EPA’s final Clean Power Plan, published in October 2015, regulates CO2 emissions from existing fossil fuel-fired electric generating resources in the continental U.S. The initial compliance start of the CPP is set for the beginning of 2022 and reaches its final emission limits in 2030.

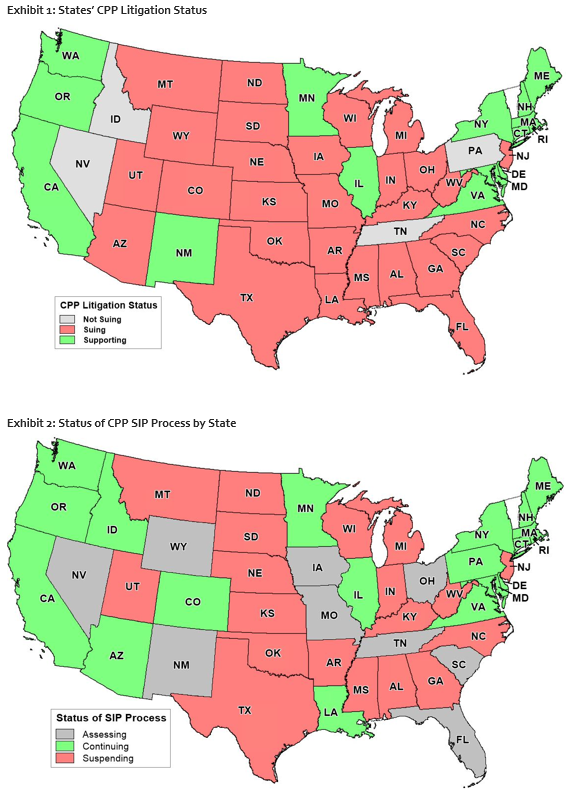

On October 23, 2015, the day EPA’s Clean Power Plan was published in the Final Register, West Virginia, along with 26 other states filed a petition to review the CPP as well as a motion to stay the rule pending the court’s decision about the rule’s legality. Which states filed the suit against the EPA, and which states are in support of the CPP is illustrated in Exhibit 1.

While the stay motion initially was denied by the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, the U.S. Supreme Court granted the stay of the Clean Power Plan on February 9, 2016, therefore freezing the implementation of the rule until the legality of the rule has been settled in court. In May 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals made the unexpected decision to bypass review by a panel of three judges in favor of considering it en-banc, meaning a review by the full U.S. Court of Appeals. Last week, on Tuesday, September 27, all 10 judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals[1] heard oral arguments for and against the legality of the CPP during a 7-hour marathon hearing.

During the over 7-hour hearing of oral arguments, three main legal questions got most attention of the 10 judges: Did the EPA overreach in its definition of Best System of Emission Reduction (BSER)? Can the EPA regulate CO2 emissions under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), while other hazard pollutants from power plants are regulated under Section 112? Did the EPA overreach by regulating the states’ power systems?

One issue that was the focus of most questions was regarding EPA’s interpretation of BSER. Petitioners argued, the EPA historically has considered BSER as something a specific power plant can achieve on-site by installing new or upgrading existing emission controls. Yet, in the CPP, the EPA defines “system” as part of BSER to be the entire U.S. electric grid (by its three interconnections – Eastern, Western, and ERCOT). By doing so, petitioners argued, EPA is forcing owners of fossil fuel burning power plants to effectively subsidize their renewable and natural gas competitors. However, the intervenors responded, due to its global impact, a larger system than just the individual plants should be considered for BSER when regulating CO2 emissions.

Another point of concern for the petitioners is EPA’s interpretation of the statutory limits of the CAA itself. Under the formulation of the CAA, emission sources covered by Section 112 of the law, which regulates hazardous air pollutants, cannot also be covered by Section 111, the foundation of the CPP, petitioners argued, and referenced two sources – a footnote by Ruth Bader Ginsburg in a SCOTUS decision in 2011, and two contradictory 1990 amendments to the CAA.

In her 2011 decision in the case AEP v. Connecticut, Supreme Court judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in a footnote that “EPA may not employ [Section 111(d)] if existing stationary sources of the pollutant in question are regulated under the national ambient air quality standard program … or the ‘hazardous air pollutants’ program, [Section 112].”

Furthermore, a 1990 CAA amendment by the House also states that the agency cannot use Section 111(d) to regulate existing power plants if they are already covered under another section of the law.

However, the Senate passed a version of the same amendment that allows for the overlap, and lawmakers did not reconcile the two different version when rushing to finalize the bill. Which version of the 1990 amendment the D.C. Circuit court deems appropriate or if it just defers to EPA’s interpretation of the law, remains to be seen.

Additionally, petitioners also raised the issue that EPA is infringing on states’ authority to regulate their electric power systems, as authorized under the Federal Power Act. By mandating wholesale changes to the power grid, EPA is infringing on that right and the power of states. Intervenors countered that EPA’s authority should stand due to its long-standing authority to regulate pollutants under the law and the fact that it has been ordered a number of times to devise a carbon regulatory system in absence of Congressional action.

When the Supreme Court decided to stay the CPP on February 9, 2016 in a 5-4 decision, many industry affiliates saw the CPP as good as thrown out. However, only four days after the CPP stay motion was granted, Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia, one of the Court’s most conservative justices and main critic of EPA’s federal overreach, died in his home state of Texas. The CPP legal case is almost guaranteed to be appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, no matter the decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals. Should the CPP case be heard in front of only eight Supreme Court justices and receive an expected split 4-4 decision, the decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals will be the ultimate legal decision on the CPP. However, most expect the next President of the United States to appoint a new Supreme Court Justice as soon as they take office in January (if not earlier should the Democratic nominee win the November election). With the U.S. Court of Appeals decision not expected until late 2016/early 2017, the Supreme Court will likely not hear the case until the beginning of the 2017 term in October, with a decision expected for late 2017/early 2018, almost two years after the rule has been stayed. This raises the probability that the Clean Power Plan case, one of the most impactful environmental regulations in EPA’s history, will be heard by a complete Supreme Court of nine judges.

Should the CPP prevail through all of its legal challenges, initial and final SIP submission deadlines along with the interim target compliance start dates are likely to be delayed by the duration of the stay of the rule. If this is the case, initial SIP submittals may be delayed to September 2018, final SIP submittals to September 2020, and interim target compliance start date to January 1st 2024. However, the final 2030 emission cap would likely remain in place with the glide path compressed over seven years.

Possible other legal outcomes include a remand by the D.C. Circuit Court to EPA to address a number of the issues such as its failure to solicit comments. Were this to occur, it would be unlikely that the Supreme Court reverses this decision and the matter would then go back to the EPA for further rulemaking, pushing back any rule by several years.

Since the stay of the CPP in February 2016, EVA has been in contact with every U.S. state subject to CPP compliance to track their respective status of their SIP development and their compliance plan preference (e.g. rate vs. mass, trading vs. no trading). Exhibit 2 shows the SIP development status by state. According to EVA’s CPP litigation and SIP tracker database, at least six Southeastern states are considering a rate-based compliance approach (FL, GA, MS, SC, TN and VA). The nine participating states of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) (CT, DE, MA, ME, MD, NH, NY, RI and VT[2]) are working towards continuing their existing closed multi-state CO2 trading system with mass-based limitations that include new sources and are stricter than the CPP’s combined limits for the nine states. They are open to expanding to include additional states willing to adopt their program cap and trade rules including (at a minimum) new sources and other non-power major stationary sources and with similarly strict mass limitations.

California also plans to continue their CO2 mass cap and trading program that also includes Quebec and possibly Ontario, which may join in 2017. However, unlike the CPP and RGGI, the California program also includes not only the power sector (both in-state and imported power) but also the transportation sector, residential heating and all stationary sources emitting above 25,000 metric tons of CO2 per year.

While most states have put their planning on hold while awaiting the outcome of the ongoing litigation, the majority of the remaining states are leaning toward adoption of a mass based limitation approach. The mass based approach is far easier to implement and enforce. Outside the RGGI and California closed CO2 trading programs, there has been general support for participation in multi-state trading programs by both state regulators and affected sources.

[1] Chief judge Merrick Garland recused himself from the case due to his consideration for filling the vacant spot on the U.S. Supreme Court.

[2] Vermont is part of RGGI, but exempt from CPP compliance.