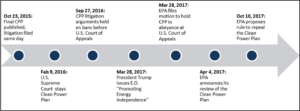

On October 10, 2017, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) added another chapter to the story of one of the most contentious environmental regulations, when EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt issued the proposed Clean Power Plan Repeal Rule. This action, almost 200 days after President Trump ordered the EPA in his Executive Order to Promote Energy Independence and Economic Growth (EO 13783) to review and as appropriate replace the CPP.

The long journey to this point begins with the inability of Congress in 2009 and 2010 to enact a carbon cap and trade program and the EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding that concluded a mix of six greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, constituted threatening air pollution under the Clean Air Act. Without a legislative alternative, the Endangerment Finding became the basis for EPA’s perceived obligation to regulate. After considerable effort, EPA developed and put forth the first draft of the CPP in 2014 and a final rule in 2015. The Clean Air Act (CAA) as amended was not a good fit for a broad carbon control plan. It provided through its various provisions the ability to regulate criteria and hazardous pollutants on individual sources through the determination of Best Available Control Technology (BACT), Reasonably Available Control Technology (RACT), and for new and modified sources in non-attainment areas, Lowest Achievable Emission Rates. (LAER). In other words, standards were applied to individual sources and based on available technology. As no commercial technology was available for CO2 reductions from existing sources, EPA got creative. EPA went beyond each source to establish a “Best System of Emission Reduction” which consisted of state-specific CO2 emission targets determined through EPA’s analysis of each state’s current and potential generation portfolio. EPA argued this was appropriate due to the interconnected and integrated nature of the U.S. electricity sector. Many (but not all) of the legal challenges to the CPP related to the BSER construct that allowed beyond the “fenceline” regulation of individual sources.

In February 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed the CPP. The Stay reflected that the majority of the Court believed (a) the legal arguments were likely to prevail and (b) irreparable harm would result if the implementation of the rule proceeded. Several events after the Stay changed the political calculus regarding this rule. The death of Justice Scalia shortly after the issuance of the Stay meant that if the Supreme Court split 4-4 on the CPP, the D.C. Circuit Court’s opinion would determine the outcome. The Senate’s refusal to consider the Obama Supreme Court nominee until after the presidential election prevented an Obama replacement from altering the make-up of the Court. The election of Donald Trump in November 2016 meant a change in direction for EPA given a major campaign promise was a reduction in burdensome regulations. (More on that here)

The proposed Clean Power Plan Repeal Rule tries to change the legal interpretation of Section 111(d) of the CAA to one that is “consistent with the [CAA’s] text, context, structure, purpose, and legislative history, as well as with the Agency’s historical understanding and exercise of its statutory authority.” Effectively, this restores EPA’s focus on “inside-the-fence” regulation. Given this interpretation, EPA proposes to repeal the rule in its entirety to be consistent with EPA’s authority.

The Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) in support of the Clean Power Plan Repeal Rule adopted the analytical framework of the previous administration, even relying on the compliance cost numbers presented in the 2015 RIA that accompanied the final CPP. However, EPA made two major changes to its analysis and how it presented the results.

First, keeping with OMB policy to only account for costs and benefits associated with domestic impacts, the EPA employed a new and much lower Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) that pertains only to domestic climate change impacts. As a result, climate benefits from the CPP fell from $20 billion in the 2015 RIA to $2.74 billion (using a 3% discount rate) in the new RIA.

Second, EPA introduced two alternative “foregone” co-benefit forecasts to emphasize the uncertainties in the RIA. One forecast is based on the assumption that there are no benefits associated with reducing ambient PM2.5 concentrations below the current National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS). The other is based on the assumption that there are no quantifiable benefits for when the PM2.5 concentration falls below the lowest measurable level as defined by two health impact studies. Varying these PM2.5 impact forecasts dramatically affects the co-benefits number. For example, PM2.5 co-benefits fall from $11.7 billion in the 2015 RIA to $1.3 billion when assuming no benefits below NAAQS levels (at 3% discount rate).

In addition to these changes, the EPA also emphasized in the new RIA that it plans to provide an additional RIA with “a more robust analysis” on which it will solicit public comment before finalizing the Repeal Rule. The EPA is not required to present a cost-benefit-analysis showing a net benefit for repealing a rule if it deems it has the sound legal footing to do so, but it seems essential to the EPA that the new RIA will show just that: a net positive of the Clean Power Plan Repeal Rule for the public.

When Administrator Pruitt proposed the publication of the Clean Power Plan Repeal Rule, he also announced that the EPA plans on publishing an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking (ANOPR) for a possible replacement rule shortly. While it seems clear that this ANOPR will focus on “inside-the-fence” CO2 regulation through process efficiency measures at the source, the exact layout of such a rule remains highly uncertain.